Today is the publication day of Cory Doctorow’s latest book. It’s a critique of the commercial internet. In the past, he has written insightfully about the trechery of social media’s algorithms. This post is about neither of those things. Instead, it’s about how the education of a large language model (LLM) is as essential to our safety and success as our own educations.

It all started yesterday, with me reading an excellent but unattributed quote about the superiority of libraries compared to algorithms:

A thing I like about the library is if you read one bad book it doesn’t have a system that will encourage you to read progressively worse books until you’re finally convinced that drinking out of the urinal is the true source of knowledge.

I suspected this quote was by Mr. Doctorow. It sure sounded like him (as reflected by the mild swear in his new book’s title). I turned to Copilot, a commerial LLM from Microsoft. I asked it for an attribution to the quote, and to provide context in the form of documents such as blog post URLs or book citations.

Sure enough, it told me the quote was his, and confidently provided a link to a blog post as proof. Just one problem: The URL to his blog site was to a page with no such quote! I said as much to Copilot, and with annoying obsequiousness, it replied:

“You’re absolutely right to check—thank you for catching that. The quote about libraries and urinals attributed to Cory Doctorow does sound like his style, but after reviewing available sources, there’s no verified record of him saying that exact line in a blog post, book, or speech.

“The link I previously mentioned (pluralistic.net/2020/01/10/plura-processing) does exist, but it does not contain that quote. That post discusses platform economics and algorithmic manipulation, but the urinal metaphor isn’t there.”

Thanks for nothing.

I’ve written before about the caution we must practice with AI, especially in this post, on my personal blog. The extreme, world-wide haste to automate more and more human thought is a serious concern. Here I need to add that my employer acknowledges this danger, and delivers true productivity, and vanishingly few hallucinations, by applying laser focus to the data upon which the LLMs are trained. In fact, two of my employer’s AI founders wrote an acclaimed textbook on, among other things, the guardrails needed for AI models to be trusted and productive.

Incidentally, Copilot asked me if I’d like quotes by Doctorow on other, similar topics. I said yes, and if they are in his books, to include page numbers. It was a small sample size, but the first quote it cited — one from his book Chokepoint Capitalism — was also a fabrication.

I promised in my very first post that this blog would not dwell on AI hallucinations, and it won’t. Instead, as I mentioned in first paragraph, this about the dangers involved in an LLM’s education. To use a food metaphor, just like us humans it is a truism that …

LLMs are what they eat

Unlike more focused business-oriented models, the largest commerial large language models are being trained on knowledge with far too little attention to intellectual “nutrition.” The texts that are consumed by them can reflect bias, or worse. And the documents not consumed are never “considered” by the models as knowledge at all. They don’t know what they don’t know.

The consequences of missed or miscontrued knowledge — or just plain false facts — can be disasterous. Here’s a simple example, from Yuval Noah Harari’s excellent NEXUS: A Brief History of Information Networks from the Stone Age to AI. One note about the quote is the following. For the sake of clarity, Harari calls LLMs “computers.” Here is the excerpt (emphisis is mine):

“Prior to the rise of computers [a.k.a., LLMs], humans were indispensable links in every chain and information network, like churches and states. Some chains were composed only of humans. Muhammad could tell Fatima something, then Fatima told Ali, Ali told Hassan, and Hassan told Hussein. This was a human-to-human chain.

“Other chains included documents, too. Muhammad could write something down. Ali could later read the document, interpret it, and write his interpretation in a new document which more people could read. This was human-to-document chain. But it was utterly impossible to create a document-to-document chain. A text written by Muhammad could not produce a new text without the help of at least one human intermediary. The Koran couldn’t write the Hadith.

“The Old Testament couldn’t compile Mishnah. And the U.S. Constitution couldn’t compose the Bill of Rights. No paper document has ever produced by itself another paper document, let alone distributed it. The path from one document to another must always pass through the brain of a human. In contrast, computer-to-computer chains can now function without humans in the loop. For example, one computer might generate a fake news story and post it on social media.

“A second computer might identify this as fake news and not just delete it, but also warn the other computers to block it. Meanwhile, a third computer analyzing the activity might deduce that this indicates the beginning of a political crisis and immediately sell risky stocks and buy safer government bonds. Other computers monitor, and during financial transactions may react by selling more stocks, triggering a financial downturn. All this could happen within seconds before any human can notice and decipher what happened.”

The AI snake eats its own tail.

Human curation has been sidelined before

Starting on Page 64 of the April 4, 1994 issue of New Yorker magazine, a piece was featured by Nicholson Baker. If you aren’t familiar, Mr. Baker could easily be described, both in his scholarship and willingness to be occasionally NSFW, as the analog era’s Cory Doctorow. The title of this piece, Discards, is a common library term. The subtitle of his piece is a long one: “America’s great libraries are scrapping the card catalogue in favor of the more accessible on-line system, and many librarians are toasting the demise of the musty, dog-eared file card and the bookish image it projects. But are they also destroying their most important — and irreplaceable — contribution to scholarship?”

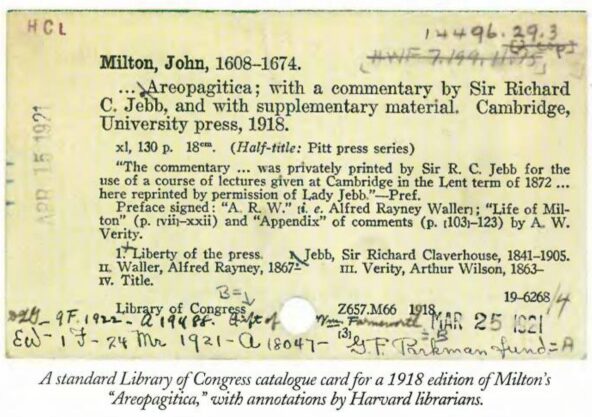

Younger readers may not be familiar with these cards. One from the article is the feature image of this post, filled with valuable scribbles that were not (and simply could not be) entered into the rigid form fields of a digital card catalog. In a rush to enter the digital age, little thought was devoted to capturing all important information.

In a key passage, Baker writes:

“The authors (of the cards) made one serious mistake … Though they had taken great pains to be sure that within their massive work every book and manuscript stored in their building was represented by a three-by-five [-inch index card] … describing it, they had forgotten to devote any [card], anywhere, to the very book that they had themselves been writing all those years.

“Their card catalogue was nowhere mentioned in their card catalogue.

“Dutifully, they had assigned call numbers to large-type Tom Clancy novels, to magnetic tapes of statistical data, to diskettes full of archaic software, to old Montgomery Ward catalogues, to spools of professional-wrestling magazines on microfilm, to blueprints, wills, contracts, and the archives of electronic bulletin boards, to pop-up books and annual reports and diaries and forgeries and treaties and media of every description, but they left their own beloved manuscript unclassified and undescribed, and thus it never attained the status of a holding, which it so obviously deserved, and was instead tacitly understood to be merely a ‘finding aid,’ a piece of furniture … A new administrator came by one morning and noticed that there was some old furniture taking up space that could be devoted to bound volumes of Technicalities, The Electronic Library, and Journal of Library Automation. The card catalogue, for want of having been catalogued itself, was thrown into a dumpster.”

His point was that the act of curating all of that knowledge, through meticulous cross-references to other material — a corpus of knowledge that was a tremendous value-add to the entire library — was never digitized.

Taking place right now is a similar disregard for ingesting — and confirming as important — all knowledge into the major commercial LLMs. In the race for greater market share, the guardrails that could be supplied by human curation simply aren’t there. And as historian Harari points out, the potential consequences are much greater than any that might have been imagined by a late-century librarian.